by Paul J. Henry

as published in the March-April 1999 issue of The Canadian Philatelist.

| On December 11th, 1936, Edward VIII, King of Great Britain, of the British Dominions and Colonies, and Emperor of India, abdicated the throne in favour of his brother Albert, the Duke of York, who became George VI. The impact on the various governments within the British Empire was untold. Edward's Coronation had been set for the 12th of May 1937. Preparations were well on their way for both his Coronation, and for the various philatelic and numismatic items which would hear his portrait. Immediately following his abdication, the governments of Great Britain and Canada moved swiftly to destroy or otherwise bury all images of Edward that had been created for the coinage, stamp, and fiduciary tender of the Realm. Preparations then began for the swift introduction of new materials to bear the portrait of the new king. |

|

Over the intervening 60 years since the events of December 1936, many theories have been raised to explain the eventual fate of the philatelic materials - the dies, proofs, and master copies[1] that were produced for the Edward VIII issue. For many years, the official word was that they were all destroyed. A.S. Deaville, chief of the Philatelic Division at the Post Office Department, writing in 1938, said:

I shall not soon forget the gloomy afternoon of the 27th of last January [1937], when a small group of Officers of the Post Office Department and the Canadian Bank Note Co. forgathered to witness defacement and destruction of the dies, transfer-roll and die-proofs that had been made in connection with the Edward VIII stamps.[2]

Robson Lowe, however, in his The Encyclopedia of British Empire Postage

Stamps, wrote that "an essay for the 3 cents value was prepared and a

die-proof in green is known". He indicates that the three-cent proof sold

at an auction in April 1971.[3]

Robson Lowe, however, in his The Encyclopedia of British Empire Postage

Stamps, wrote that "an essay for the 3 cents value was prepared and a

die-proof in green is known". He indicates that the three-cent proof sold

at an auction in April 1971.[3]

Finally, in an article published in a 1978 issue of BNA Topics, Jim

Kraemer, then Manager of the National Postal Museum in Ottawa, wrote: "The

3-cent die-proof which has been attributed to the King Edward VIII issue (Robson

Lowe's Encyclopedia, vol. V, p.261) is in fact an early stage in the production

of the King George VI issue, for which the first model was produced on 21

January 1937."[4]

Finally, in an article published in a 1978 issue of BNA Topics, Jim

Kraemer, then Manager of the National Postal Museum in Ottawa, wrote: "The

3-cent die-proof which has been attributed to the King Edward VIII issue (Robson

Lowe's Encyclopedia, vol. V, p.261) is in fact an early stage in the production

of the King George VI issue, for which the first model was produced on 21

January 1937."[4]

A two-cent die-proof. in red, was to appear in the 1990 American Bank Note Co. Archives sale, and later at CAPEX '96 (the premier philatelic exhibition held in Toronto in June 1996).[5]

It is the purpose of this paper to examine the events surrounding the demise of the Edward VIII issue, and its connection to the first George VI issue, and to clarify the status of the die-proof essays relating to Edward.

George V died on 20 January 1936. On 23 January, a memorandum was prepared by the Canadian Post Office Authorities questioning previous practice "in regard to previous issues on the accession of a new Monarch."[6]

By appealing to precedence, the post office hoped to alleviate any problems with new stamp issues. In the case of George V, there were already a large supply of stamps ready for issue. "Considerations of respect to the deceased sovereign, and less sentimental motivations of expediency and economy" usually dictate that a certain period of time expire before the issuing of a new stamp bearing the portrait of the new king becomes necessary. In addition, in both cases where a sovereign seceded to the throne, since the introduction of postage stamps, no stamp issue was made before their coronation.[7]

The process by which a postage stamp is prepared, approved, and finally printed, is a long one. In the case of Edward, it was the wish of the king that only an authorized portrait be used.

On 27 January 1936, the Post Office Department contacted the under-secretary of State to obtain an authorized portrait. The State Office then contacted London to determine what portraits were available, and make the necessary arrangements. At that time, post office officials were concerned as to whether they would have to wait until after the Coronation to issue new stamps. It was soon decided, however, to proceed with the request to obtain an authorized photograph. A letter was soon drafted and sent from the office of J.C. Elliot, Postmaster General, to Vincent Massey, High Commissioner for Canada in Britain.

On 27 March, Mr. Massey replied that he had been in touch with the Private Secretary to the King, and that a photograph was forthcoming. Six days later, a confidential letter was received by the Postmaster General from Massey, with a copy of the photograph enclosed. Accompanying the photograph was a memorandum from the Private Secretary to the king, indicating that the King wished to approve any designs. Although this approval was requested, it was not required. Writing to the Postmaster General, H.E. Atwater, the Post Office Department Financial Superintendent indicated that:

There is nothing in the Canadian statutes to require that the King should personally approve of designs used in Canadian postage stamps. This practice seems to have been followed as a matter of courtesy to the reigning Monarch for a considerable number of years.[8]

It was estimated in April that it would take "up to six months to print the necessary stock".[9]

On 19 May, the approved photograph was submitted to the Canadian Bank Note Co.. the firm responsible for the printing of all Canadian stamps and currency during this period. At the same time. on 30 May, a letter was sent to the Master of the Royal Mint from the Post Office Department, requesting another photograph of the King, this one a photograph of the design used to create Canadian coinage.[10]

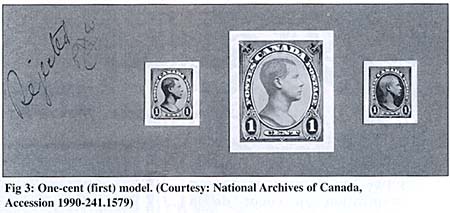

The approved photograph, in the meantime, was used to create a model, and on

22 June 1936, it was submitted to the Post Office Department. On 29 July, the

model was returned to the Canadian Bank Note Co.[11] due to defects. "There

is just one criticism which might be warranted. namely, that there is too much

of the neck and shoulder showing," wrote Atwater to P.J. Wood,

vice-president of the Canadian Bank Note Co.[12] Its return was anticipated,

however, as the bank note company had already been hard at work on its second

model using the photograph obtained from the Mint. Writing on 15 June to his

colleague H.R. Treadwell of the American Bank Note Co., P.J. Wood said:

"...the indications are the Government will not use the profile portrait of His Majesty King Edward VIII which He supplied for making a model and within three or four months will furnish us with a coin bearing a medallion picture of His Majesty to be used by the engraver.[13]

By 10 August, the Canadian Bank Note Co. informed the Post Office Department

that the second model was well underway. It was to be a similar design, with the

changes suggested by Atwater. The post office had been concerned that since the

first stamp issue of a new Sovereign is the most scrutinized, the proportions on

the stamp should be as clean as possible.[14] This design featured a profile of

Edward with a shorter neck, and facing to the right.

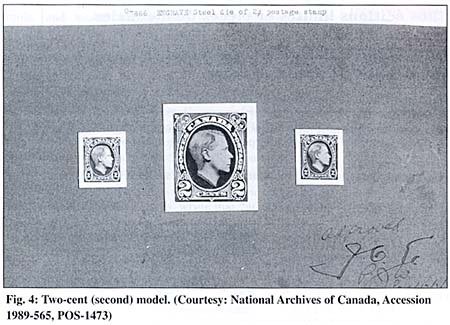

For the second model, a one-cent and two-cent design was created.[15]

On 24 August the two-cent model was submitted to the Post Office Department

by the Canadian Bank Note Co., and it was forwarded to the Deputy Postmaster

General by H.E. Atwater.[16]

On 10 September, a memorandum from PT. Cooligan, the Assistant Deputy Postmaster General, indicated that the design was approved in principle, however, several changes were to be made, including a partial redesign of the crown and its placement in the upper right and left corners. and a directive that the King's head by reversed. Says Cooligan:

It is recommended that the Canadian design should be changed to face the left for the reason that the parting of the King's hair appears on the right whereas he actually parts it on the left.[17]

He further notes that although it was reported that as each succeeding Sovereign comes to the throne, the position of the head on stamps and coins is reversed, this was not necessarily the case. These instructions were conveyed to the Canadian Bank Note Co., and an internal order sheet, dated 14 September 1936, requested that changes be made to the two-cent model.[18]

By 16 October, it was clear that the Post Office Department wished to use the plaster cast utilized by the Mint, and on I 9 October, the Postmaster General wrote the High Commissioner in London requesting the plaster cast.[19] It is this model, sculpted by British designer Hugh Paget, that eventually was to he used for the stamps bearing Edward's profile. The model is about 10 inches in diameter, formed from a mixture of artists' powder and metal. It depicts Edward VIII in uncrowned effigy. Two of these models were delivered to Canada, one to the Canadian Mint and the other, eventually, to the Postmaster General's office for delivery to the Canadian Bank Note Co.[20]

Both of these models were to be saved from destruction, however, the first by Emmanuel Hahn the engraver of Canada's Edward VIII coinage, and the second by A.S. Deaville of the Post Office Department. Deaville's copy was to be acquired by the Nickle Foundation in 1965. and is now displayed in the Glenbow in Calgary.[21]

On 20 November 1936, Percy Wood of the Canadian Bank Note Co. wrote his

colleague, Mr. Treadwell at the American Bank Note Co. in New York,

acknowledging the receipt of two die impressions, from dies engraved by Edwin

Gunn, of the third (approved) two-cent model, one in #53 green, and the other in

red, as well as an original photograph of the plaster cast which was to be used

by the engravers to create yet another die impression.[22] Four days later, the

improved design was submitted to the Post Office Department for consideration.

Wrote Wood to Atwater, "we believe you will agree we have engraved a true

likeness of His Majesty as it appears on the medal and we sincerely trust that

the proof will meet with your approval".[23]

On 20 November 1936, Percy Wood of the Canadian Bank Note Co. wrote his

colleague, Mr. Treadwell at the American Bank Note Co. in New York,

acknowledging the receipt of two die impressions, from dies engraved by Edwin

Gunn, of the third (approved) two-cent model, one in #53 green, and the other in

red, as well as an original photograph of the plaster cast which was to be used

by the engravers to create yet another die impression.[22] Four days later, the

improved design was submitted to the Post Office Department for consideration.

Wrote Wood to Atwater, "we believe you will agree we have engraved a true

likeness of His Majesty as it appears on the medal and we sincerely trust that

the proof will meet with your approval".[23]

On 1 December 1936, after receiving approval of the Postmaster General and

Governor in Council, the Canadian Bank Note Co. was requested to submit a

die-proof for forwarding to His Majesty. On that same day a two-cent die-proof,

in brown, also received approval, and was returned to the Canadian Bank Note Co.

by the Post Office Department.[24] Within four days, on 5 December 1936,

die-proof XG-626 (a two-cent in red) was sent to England aboard the S.S.

Lancastria.[25] Six days later, another die-proof, XG-632, this one a three-cent

(also in red) was sent to England.

On 1 December 1936, after receiving approval of the Postmaster General and

Governor in Council, the Canadian Bank Note Co. was requested to submit a

die-proof for forwarding to His Majesty. On that same day a two-cent die-proof,

in brown, also received approval, and was returned to the Canadian Bank Note Co.

by the Post Office Department.[24] Within four days, on 5 December 1936,

die-proof XG-626 (a two-cent in red) was sent to England aboard the S.S.

Lancastria.[25] Six days later, another die-proof, XG-632, this one a three-cent

(also in red) was sent to England.

Unfortunately, while the die-proofs were still at sea, Edward VIII abdicated. The Post Office Department quickly telegrammed Massey to request that he return them as soon as they were received, which he did.[26]

Meanwhile, the Post Office Department was running out of stamps in stock. In a letter dated 9 December, H.E. Atwater queried T.R. Legault of the accounting department to determine the number of stamps available for issue.[27] The next day, Legault replied that there were approximately 146 million stamps in the one-, two-, and three-cent denominations, and 12 million of other denominations.[28] This amounted to only three to four months supply of the lower denominations. On 15 December, Atwater directed Legault to control distribution until the situation could be remedied.[29]

Reaction to the events of II December was varied. In an article in The

Morning Citizen. on 14 December 1936, it was reported that Britain would

continue to print King Edward VIII stamps.[30] In Canada, however, the Rt. Hon.

W.L. Mackenzie King took the King’s abdication as a personal affront.

Accordingly, instructions were given from the Prime Minister that, "every

vestige of the now abhorred Edward's image was to be destroyed."[31]

Atwater, in the meantime, had proposed that the Post Office Department go ahead

with the distribution of Edward VIII stamps, due to the dwindling supply of

George V stamps. and the fact that the new stamp was ready for production. He

argued that releasing a stamp bearing a portrait of Edward VIII would not be out

of the question due to the fact that the post office continued to issue stamps

for many months after the death of a reigning Monarch. He believed that a

limited distribution of 200 million stamps would suffice in order to give the

Canadian Bank Note Co. sufficient time to produce a stamp bearing the portrait

of George VI.[32] His plan was to remain unrealized.

Reaction to the events of II December was varied. In an article in The

Morning Citizen. on 14 December 1936, it was reported that Britain would

continue to print King Edward VIII stamps.[30] In Canada, however, the Rt. Hon.

W.L. Mackenzie King took the King’s abdication as a personal affront.

Accordingly, instructions were given from the Prime Minister that, "every

vestige of the now abhorred Edward's image was to be destroyed."[31]

Atwater, in the meantime, had proposed that the Post Office Department go ahead

with the distribution of Edward VIII stamps, due to the dwindling supply of

George V stamps. and the fact that the new stamp was ready for production. He

argued that releasing a stamp bearing a portrait of Edward VIII would not be out

of the question due to the fact that the post office continued to issue stamps

for many months after the death of a reigning Monarch. He believed that a

limited distribution of 200 million stamps would suffice in order to give the

Canadian Bank Note Co. sufficient time to produce a stamp bearing the portrait

of George VI.[32] His plan was to remain unrealized.

In a letter to philatelist A.F. Brophy in Montreal, on 16 December, Atwater expressed his frustration at the process, 'You can imagine the state we are in at the present time due to the abdication of King Edward VIII. We now have to consider a new issue for the new King."[33] Writing on 4 January 1937, a saddened Atwater reported to Colonel George P. Vanier, Secretary to the High Commission in London, that:

The Government has decided not to issue any King Edward VIII stamps, and for that reason it is necessary to discontinue all work on the engraving of dies and printing plates. As you may be aware, all dies not used for stamp issues are destroyed.[34]

Atwater, however, did not wish to see any of the material used in the production of the Edward stamp wasted, and on II January, in a letter to Percy Wood of the Canadian Bank Note Co., he indicated that he was in the process of trying to get the authority to use the design of the King Edward stamp, with only the portrait of the King changed. This action was later approved, and the frame created for the Edward VIII stamp issue was incorporated into the design for the George VI issue.[35]

The proofs, dies, and master copies, however, were to be destroyed, as per the orders of the Government of Canada.

On 22 January 1937, PJ. Wood wrote to Atwater indicating those proofs on hand, as approved on 27 November 1936. Three days later, on 25 January, fifty-two of the XG-626 die-proofs were cremated, and witnessed by Arnold Reece, Manager of the Engraving department, with the remaining die-proofs, dies, and transfer rolls[36] destroyed on 27 January in the presence of numerous officials, including Atwater, Wood, and Deaville.[37]

How die-proof XG-626 survived this destruction order is not known. The only possibility is that this die-proof was one of the three die-proofs (one in red, one in green, and one in brown) transferred to the Canadian Bank Note Co. by the Post Office Department on 20 January 1937 to assist in the production of the George VI stamp.[38] If the die-proof which appeared at CAPEX '96 was one of these three die-proofs, then this would suggest that two more die-proofs of the two-cent model (one in green and one in brown) might yet exist.

The three-cent green die-proof (as illustrated in Robson Lowe's Encyclopedia, vol. V, p.261) may very well be (due to its lack of an XG number) a progressive die-proof, submitted to the Post Office Department on 4 December 1936[39], and approved 11 December l936.[40] If any die-proofs of the three-cent survived, they would have been XG-632,[41] but we know from a letter from Wood to Atwater on 22 January 1937 that only one die-proof using the XG-632 die was ever made, and this was a three-cent in red, destroyed on 27 January along with the XG-626 proofs.[42] Thus, the only remaining die-proof of the three-cent is the Robson Lowe progressive die-proof, in green.

(Paul J. Henry is an archivist and historical researcher He has worked at the Canadian Postal Archives at the National Archives of Canada, and currently teaches applied archival studies at Algonquin College. He lives in Ottawa).

|

1 For an excellent glossary of philatelic terms, see Ken Wood's This

is Philately, 3 vols., Van Dahl, Albany, OR, 1982. 2 A. Stanley Deaville, "Canadian stamps that might have been", Weekly Philatelic Gossip, vol. 27, no 22 (1939), pp.594. 3 The Encyclopedia of British Empire Postage Stamps: 1639-1952, Vol. V: The Empire in North America, Robson Lowe Ltd., London, 1973, p.261. The proof sold for £57.50. 4 From P0. Archives: The story of the proposed King Edward VIII issue of Canada", BNA Topics, vol.35, no 2 (March-April, 1978), p.9. 5 As reported in Ian S. Robertson's "The Man who would not be King", in Canadian Stamp News, June 25, 1996, p.5. The proof was purchased by stamp dealer John Jamieson of Saskatoon Stamps. 6 Memorandum re: Action taken leading up to issue of new King Edward VIII stamps", II December 1936, File 13-13-12, PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 7 Deaville, p.594. 8 Memorandum for Postmaster General", II December 1936, File 13-13-12, PSE-Edward VIII. National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 9 Memorandum re: Action taken leading up to issue of new King Edward VIII stamps", II December 1936. File 13-13-12. PSE-Edward VIII. National Postal Museum research file series. Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 10 Ibid. 11 The Canadian Bank Note Co. was established by the American Bank Note Co. of New York in 1897. On 1 January 1923, it acquired all business. property, assets, and contracts with the Dominion government. It became wholly Canadian-owned in 1976. During the 1930s, Canadian Bank Note Co. was responsible only for the printing of the stamps; the engraving and design work was done in New York. 12 H.E. Atwater to RJ. Wood, 29 July 1936, File 13-13-12. PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565. National Archives of Canada. 13 RJ. Wood to H.R. Treadwell letter, 15 June 1936, Lot 2046, Accession 1990-241, National Archives of Canada. 14 Atwater, "Memorandum for the Deputy Postmaster General", 5 August 1936, File 13-13-12, PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 15 Design 0-861, 1-cent Edward profile with vignette, also facing right and bearing the date 31 July 1936. (NAINI-l5, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada). Design 0-866, 2-cent Edward profile with vignette, facing right, 20 August 1936, Lot 2045, Accession 1990-241. 16 "Memorandum re: Action taken leading up to issue of new King Edward VIII stamps", II December 1936, File 13-13-12, PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 17 PT. Cooligan, Memorandum, 10 September 1936, PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 18 Canadian Bank Note Co., Order sheet for design 0-866, 14 September 1936, Lot 2046, Accession 1990-241, National Archives of Canada. 19 "Memorandum re: Action taken leading up to issue of new King Edward VIII stamps", 11 December 1936, File 13-13-12, PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 20 The Nickle Foundation, "The Master Model - for Edward VIII coinage & stamps for Canada, 1937", PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada.

|

21 The Nickle Foundation, "Numismatic Relics of King Edward VIII",

PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession

1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 22 Wood to Treadwell, 20 November 1936, Lot 2046, Accession 1990-241, National Archives of Canada. 23 Wood to Atwater, 24 November 1936, File 13-13-12, PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 24 Letter Atwater to Wood, 1 December 1936, File 13-13-12, Vol.3378, RO 3, National Archives of Canada. 25 "From P0. Archives: The story of the proposed King Edward VIII issue of Canada", BNA Topics, March-April, 1978, p.7. 26 Ibid. 27 Letter HE. Atwater to T.R. Legault, 9 December 1936, File 13-I 3-2, Vol.3843, RG 3, National Archives of Canada. 28 Letter Legault to Atwater. 10 December 1936, File 13-13-2. Vol.3843, RG 3. National Archives of Canada. 29 Letter Atwater to Legault. 15 December 1936, File 13-I 3-2, Vol.3843, RG 3. National Archives of Canada. 30 "Continue Printing King Edward Stamps", The Morning Citizen, 14 December 1936, File 13-13-13. Vol.3843, RG 3, National Archives of Canada. 31 The Nickle Foundation. "The Master Model - for Edward VIII coinage & stamps for Canada. 1937". PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research tile series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 32 Atwater, "Memorandum for Postmaster General", II December 1936, File 13-13-12. PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565. National Archives of Canada. 33 Letter Atwater to A.F Brophy, 16 December 1936, File 13-13-13, Vol. 3843, RG 3, National Archives of Canada. 34 Atwater to Vanier, 4 January 1937, File 13-13-12, PSE-Edward VIII, National Postal Museum research file series, Accession 1989-565, National Archives of Canada. 35 George VI one-, two-, and three-cent models, Order 0-876, Lot 2049, Accession 199 (1-241, National Archives of Canada. See also Atwater to Wood, 20 January 1937, File 13-13-12, Vol.3843, RG 3, National Archives of Canada. 36 No plates were ever made (Wood to Atwater, 23 January, 1937, File 13-13-12). The die-proofs destroyed were: two 2c in brown, two 2c in green, three 2c in red, and one 3c in red. 37 "From P.O. Archives: The story of the proposed King Edward VIII issue of Canada", BNA Topics. March-April, 1978, p.9. 38 Atwater to Wood. 20 January 1937, File 13-13-12, Vol.3378, RG 3, National Archives of Canada. 39 Wood to Atwater, 4 December 1936, File 13-13-12, Vol.3378, RG 3, National Archives of Canada. 40 Dies, rolls, plates memo. 9 January 1937, File 13-13-12, Vol.3378, RO 3, National Archives of Canada. 41 Ibid. 42 Wood to Atwater, 22 January 1937, File 13-13-12, Vol.3378, RO 3, National Archives of Canada. The 3c die-proof was sent from Ottawa the night of 11 December 1936, and referred to in a letter from Vincent Massey (High Commissioner for Canada), dated 21 December 1936. (File 13-13-12) It was returned to Ottawa with Massey's letter.

|